Flipping Pages: An analysis of a new Linux vulnerability in nf_tables and hardened exploitation techniques

A tale about exploiting KernelCTF Mitigation, Debian, and Ubuntu instances with a double-free in nf_tables in the Linux kernel, using novel techniques like Dirty Pagedirectory. All without even having to recompile the exploit for different kernel targets once.

This blogpost is the next instalment of my series of hands-on no-boilerplate vulnerability research blogposts, intended for time-travellers in the future who want to do Linux kernel vulnerability research. Specifically, I hope beginners will learn from my VR workflow and the seasoned researchers will learn from my techniques.

In this blogpost, I'm discussing a bug I found in nf_tables in the Linux kernel (CVE-2024-1086) and its root cause analysis. Then, I show several novel techniques I used to drop a universal root shell on nearly all Linux kernels between at least v5.14 and v6.6.14 (unpriv userns required) without even recompiling the exploit. This is possible because of the data-only, KSMA ambience of the exploit. Among those targeted kernels are Ubuntu kernels, recent Debian kernels, and one of the most hardened Linux kernels out there (KernelCTF mitigation kernels).

Additionally, I'm providing the proof-of-concept source code (also available in the CVE-2024-1086 PoC repository on Github). As a bonus, I wanted to challenge myself by making the exploit support fileless execution (which helps in CNO and avoids detections in pentests), and by not making any changes to the disk whatsoever (including setting /bin/sh to SUID 0 et cetera).

This blogpost aims to be a supplementary guide to the original Dirty Pagetable blogpost as well, considering there were not any blogposts covering the practical bits (e.g. TLB flushing for exploits) when I started writing this blogpost. Additionally, I hope the skb-related techniques will be embedded in remote network-based exploits (e.g. bugs in IPv4, if they still exist), and I hope that the Dirty Pagedirectory technique will be utilized for LPE exploits. Let's get to the good stuff!

0. Before you read

0.1. How to read this blogpost

To the aspiring vulnerability researchers: I wrote this blogpost in a way that slightly represents a research paper in terms of the format, because the format happens to be exactly what I was looking for: it is easy to scan and cherrypick knowledge from even though it may be a big pill to swallow. Because research papers are considered hard to read by many people, I'd like to give steps on how I would read this blogpost to extract knowledge efficiently:

- Read the overview section (check if the content is even interesting to you)

- Split-screen this blogpost (reading and looking up)

- Skip to the bug section (try to understand how the bug works)

- Skip to the proof of concept section (walk through the exploit)

If things are not clear, utilize the background and/or techniques section. If you want to learn more about a specific topic, I have attached an external article for most sections.

0.2. Affected kernel versions

This section contains information about the affected kernel versions for this exploit, which is useful when looking up existing techniques for exploiting a bug. Based on these observations, it seems feasable that all versions from atleast (including) v5.14.21 to (including) v6.6.14 are exploitable, depending on the kconfig values (details below). This means that at the time of writing, the stable branches linux-5.15.y, linux-6.1.y, and linux-6.6.y are affected by this exploit, and perhaps linux-6.7.1 as well. Fortunately for the users, a bugfix in the stable branches has been released in February 2024.

Note that the same base config file was reused for most vanilla kernels, and that the mentioned versions are all vulnerable to the PoC bug. The base config was generated with kernel-hardening-checker. Additionally, if a version isn't affected by the bug, yet the exploitation techniques work, it will not be displayed in the table.For vanilla kernels, CONFIG_INIT_ON_FREE_DEFAULT_ON was toggled off in the config, which sets a page to null-bytes after free - which thwarts the skb part of for the exploit. This config value is toggled off in major distro's like KernelCTF, Ubuntu, and Debian, so I consider this an acceptable measure. However, CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON remains toggled on, as this is part of the Ubuntu and Debian kernel config. Unfortunately, this causes bad_page() detection as an side-effect in versions starting from v6.4.0. When CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON is toggled off, the exploit is working up to (including) v6.6.4.

The success rate for the exploit is 99.4% (n=1000) - sometimes with drops to 93.0% (n=1000) - on Linux kernel v6.4.16, with the setup as below (and the kernelctf filesystem). I do not expect the success rate to deviate much across versions, although it might deviate per device workload. I consider an exploit working for a particular setup if it succeeds all attempts at trying it out (manual verification, so usually 1-2 tries). Because of the high success rate, it is pretty easy to filter out if the exploit works or not. Additionally, all fails have been investigated and hence have their reasons been included in the table, so false positives are unlikely.

All non-obsolete techniques (and the resulting PoC) are tested on setups:

| Kernel | Kernel Version | Distro | Distro Version | Working/Fail | CPU Platform | CPU Cores | RAM Size | Fail Reason | Test Status | Config URL |

|--------|----------------|-----------|-------------------|--------------|-------------------|-----------|----------|---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-------------|------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Linux | v5.4.270 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [CODE] pre-dated nft code (denies rule alloc) | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.4.270.config |

| Linux | v5.10.209 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [TCHNQ] BUG mm/slub.c:4118 | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.10.209.config |

| Linux | v5.14.21 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.14.21.config |

| Linux | v5.15.148 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.15.148.config |

| Linux | v5.16.20 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.16.20.config |

| Linux | v5.17.15 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.17.15.config |

| Linux | v5.18.19 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.18.19.config |

| Linux | v5.19.17 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v5.19.17.config |

| Linux | v6.0.19 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.0.19.config |

| Linux | v6.1.55 | KernelCTF | Mitigation v3 | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-kernelctf-mitigationv3-v6.1.55.config |

| Linux | v6.1.69 | Debian | Bookworm 6.1.0-17 | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-debian-v6.1.0-17-amd64.config |

| Linux | v6.1.69 | Debian | Bookworm 6.1.0-17 | working | AMD Ryzen 5 7640U | 6 | 32GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-debian-v6.1.0-17-amd64.config |

| Linux | v6.1.72 | KernelCTF | LTS | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-kernelctf-lts-v6.1.72.config |

| Linux | v6.2.? | Ubuntu | Jammy v6.2.0-37 | working | AMD Ryzen 5 7640U | 6 | 32GiB | n/a | final | |

| Linux | v6.2.16 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.2.16.config |

| Linux | v6.3.13 | n/a | n/a | working | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | n/a | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.3.13.config |

| Linux | v6.4.16 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [TCHNQ] bad page: page->_mapcount != -1 (-513), bcs CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON=y | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.4.16.config |

| Linux | v6.5.3 | Ubuntu | Jammy v6.5.0-15 | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [TCHNQ] bad page: page->_mapcount != -1 (-513), bcs CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON=y | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-ubuntu-jammy-v6.5.0-15.config |

| Linux | v6.5.13 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [TCHNQ] bad page: page->_mapcount != -1 (-513), bcs CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON=y | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.5.13.config |

| Linux | v6.6.14 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [TCHNQ] bad page: page->_mapcount != -1 (-513), bcs CONFIG_INIT_ON_ALLOC_DEFAULT_ON=y | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.6.14.config |

| Linux | v6.7.1 | n/a | n/a | fail | QEMU x86_64 | 8 | 16GiB | [CODE] nft verdict value incorrect is altered by kernel | final | https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Notselwyn/blogpost-files/main/nftables/test-kernel-configs/linux-vanilla-v6.7.1.config |Table 0.2.1: An overview of the exploit test results per tested kernel versions and their setups.

1. Overview

1.1. Abstract

In this blogpost I present several novel techniques I used to exploit a 0-day double-free bug in hardened Linux kernels (i.e. KernelCTF mitigation instances) with 93%-99% success rate. The underlying bug is input sanitization failure of netfilter verdicts. Hence, the requirements for the exploit are that nf_tables is enabled and unprivileged user namespaces are enabled. The exploit is data-only and performs an kernel-space mirroring attack (KSMA) from userland with the novel Dirty Pagedirectory technique (pagetable confusion), where it is able to link any physical address (and its permissions) to virtual memory addresses by performing just read/writes to userland addresses.

1.2. Workflow

To trigger the bug leading to the double-free, I add a Netfilter rule to an unprivileged-user namespace. The Netfilter rule contains an expression which sets a malicious verdict value, which will make the internal nf_tables kernel code interpret NF_DROP at first, after which it will free the skb, and then return NF_ACCEPT so the packet handling continues, and it will double-free the skb. Then, I trigger this rule by allocating an 16-page IP packet (so that it gets allocated by the buddy-allocator and not the PCP-allocator or slab-allocator, and it shares a cache across CPUs) which has migratetype 0.

In order to delay the 2nd free (so I can avoid corruption by doing stuff), I abuse the IP fragmenation logic of an IP packet. This allows us to make an skb "wait" in an IP fragmentation queue without being freed for an arbitrary amount of seconds. In order to traverse this code path with corrupted packet metadata, I spoof IP source address 1.1.1.1 and destination address 255.255.255.255. However, this means we get to deal with Reverse Path Forwarding (RPF), so we need to disable it in our networking namespace (does not require root privileges).

To achieve unlimited R/W to any physical memory address (including kernel addresses), I present the Dirty Pagedirectory technique. This technique is - softly said - pagetable confusion, by allocating an PTE page and PMD page to the same physical page.

Unfortunately, these pagetable pages are migratetype==0 order==0 pages allocated with alloc_pages(), and skb heads (the double-free'd objects) are allocated with kmalloc, which means the slab-allocator is used for page order<=1, the PCP-allocator is used for order<=3, and the buddy-allocator for order>=4. To avoid hassle (explained in detail in the blogpost), we have to use order>=4 pages for the double-free. This also means we cannot directly use a double-free on buddy-allocator pages (order>=4) to double allocate PTE/PMD pages (order==0), but I discovered methods to achieve this.

To double allocate PTE/PMD pages with the kmalloc-based double-free, I present 2 methods:

The better page conversion technique (PCP draining)

In this simpler, more stable, and faster method we take advantage of the fact that the PCP-allocator is simply a per-CPU freelist, which is refilled with pages from the buddy-allocator when it is drained. Hence, we can simply free order==4 (16) pages to the buddy-allocator freelist, drain the PCP list, and refill the order==0 PCP list with 64 pages from the buddy-allocator freelist, containing said 16 pages.

The original page conversion technique (racecondition)

This method relies on a race-condition and hence only works in virtualized environments such as QEMU VMs, where terminal IO causes a substantial delay in the VMs kernel. We take advantage of a WARN() message which causes ~50-300ms delay to trigger a race condition, to free an order==4 buddy page to an order==0 PCP freelist. As you may notice, this does not work on real hardware (as the delay is ~1ms) and is therefore replaced with the method above. Unfortunately, I used this technique for the original kernelctf exploit.

Between the double-free, I make sure the page refcounts never go to 0 since it would deny freeing the page (possibly as a double-free mitigation). Additionally, I spray skb objects into the skbuff_head_cache slabcache of the same CPU to avoid experimental freelist corruption detection in the kernelctf mitigation instance, and to increase stability in general.

When the double-free primitive is achieved, I will use a new technique called Dirty Pagedirectory to achieve unlimited read/write to any physical address. This requires double-allocating a page table entry (PTE) page and a page middle directory (PMD) page to the same address. When writing an arbitrary PTE value containing page permissions and page physical address to a page within the span of the PTE page, the PMD page will interpret said address when trying to dereference the PTE value's page within the PMD pages' span. This boils down to setting a PTE value to 0xDEADBEEF entirely from userland, and then dereference that PTE value from userland again to access the page referenced to by 0xDEADBEEF using the flags (including but not limited to permissions) set in 0xDEADBEEF.

In order to utilize this unlimited R/W primitive, we need to flush the TLB. After reading several impractical research papers I came up with my own complex flushing algorithm to flush TLBs in Linux from userland: calling fork() and munmap()'ing the flushed VMA. In order to avoid crashes when the child exits the program, I make the child thread go to sleep indefinitely.

I utilize this unlimited physical memory access to bruteforce physical KASLR (which is accelerated because the physical kernel base is aligned with CONFIG_PHYSICAL_START (a.k.a. 0x100'0000 / 16MiB) or - when defined - CONFIG_PHYSICAL_ALIGN (a.k.a. 0x20'0000 / 2MiB) and leak the physical kernel base address by checking 2MiB worth of pages on a machine with 8GiB memory (assuming 16MiB alignment), which even fits into the area of a single overwritten PTE page. To detect the kernel, I used the get-sig scripts which generate a highly precise fingerprint of files, like recent Linux kernels across compilers, and slapped that into my exploit.

In order to find modprobe_path, I do a fairly simplistic "/sbin/modprobe" + "\x00" * ... memory scan across 80MiB beyond the detected kernel base to get access to modprobe_path. To verify that the "real" modprobe_path variable was found instead of a false-positive, I overwrite modprobe_path and check if /proc/sys/kernel/modprobe (read-only user interface for modprobe_path) reflects this change. If CONFIG_STATIC_USERMODEHELPER is enabled, it will just check for "/sbin/usermode-helper".

In order to drop a root shell (including an namespace escape) I overwrite modprobe_path or "/sbin/usermode-helper" to the exploits' memfd file descriptor containing the privesc script, such as /proc/<pid>/fd/<fd>. This fileless approach allows the exploit to be ran on an entire read-only filesystem (it being bootstrapped using perl). The PID has to be bruteforced if the exploit is running in a namespace - because the exploit only knows the namespace PID - but is luckily incredibly fast since we don't need to flush the TLB as we aren't changing the physical address of the PTE. This will essentially be writing the string to a userland address and executing a file.

In the privesc script, we will execute a /bin/sh process (as root) and hook the exploits' file descriptors (/dev/<pid>/fd/<fd>) to the shells' file descriptors, allowing us to achieve a namespace escape. The advantage of this method is that it's very versatile, as it works on local terminals and reverse shells, all without depending on filesystems and other forms of isolation.

2. Background info

2.1. nf_tables

One of the in-tree Linux kernel modules is nf_tables. In recent versions of iptables - which is one of the most popular firewall tools out there - the nf_tables kernel module is the backend. iptables itself is part of the ufw backend. In order to decide which packets will pass the firewall, nftables uses a state machine with user-issued rules.

2.1.1. Netfilter Hierarchy

These rules come in the following orders (i.e. one table contains many chains, one chain contains many rules, one rule contains many expressions):

- Tables (which protocol)

- Chains (which trigger)

- Rules (state machine functions)

- Expressions (state machine instructions)

This allows users to program complex firewall rules, because nftables has many atomic expressions which can be chained together in rules to filter packets. Additionally, it allows chains to be ran at different times in the packet processing code (i.e. before routing and after routing) which can be selected when creating a chain using flags like NF_INET_LOCAL_IN and NF_INET_POST_ROUTING. Due to this extremely customizable nature, nftables is known to be incredibly insecure. Hence, many vulnerabilities have been reported and have been fixed already.

To learn more about nftables, I recommend this blogpost by @pqlqpql which goes into the deepest trenches of nftables: "How The Tables Have Turned: An analysis of two new Linux vulnerabilities in nf_tables."

2.1.2. Netfilter Verdicts

More relevant to the blogpost are Netfilter verdicts. A verdict is a decision by a Netfilter ruleset about a certain packet trying to pass the firewall. For example, it may be a drop or an accept. If the rule decides to drop the packet, Netfilter will stop processing the packet. On the contrary, if the rule decides to accept the packet, Netfilter will continue processing the packet until the packet passes all rules. At the time of writing, all the verdicts are:

- NF_DROP: Drop the packet, stop processing it.

- NF_ACCEPT: Accept the packet, continue processing it.

- NF_STOLEN: Stop processing, the hook needs to free it.

- NF_QUEUE: Let userland application process it.

- NF_REPEAT: Call the hook again.

- NF_STOP (deprecated): Accept the packet, stop processing it in Netfilter.

2.2. sk_buff (skb)

To describe network data (including IP packets, ethernet frames, WiFi frames, etc.) the Linux kernel uses the sk_buff structure and commonly calls them skb's as shorthand. To represent a packet, the kernel uses 2 objects which are important to us: the sk_buff object itself which contains kernel meta-data for skb handling, and the sk_buff->head object which contains the actual packet content like the IP header and the IP packets' body.

In order to use values from the IP header (since IP packets are parsed in the kernel afterall), the kernel does type punning with IP header struct and the sk_buff->head object using ip_hdr(). This pattern gets applied across the kernel since it allows for quick header parsing. As a matter of fact, the type punning trick is also used to parse ELF headers when executing a binary.

To learn more, check this excelent Linux kernel documentation page: "struct sk_buff - The Linux Kernel."

2.3. IP packet fragmentation

One of the features of IPv4 is packet fragmentation. This allows packets to be transmitted using multiple IP fragments. Fragments are just regular IP packets, except that they do not contain the full packet size specified in its IP header and it having the IP_MF flag set in the header.

The general calculation for the IP packet length in an IP fragments' header is iph->len = sizeof(struct ip_header) * frags_n + total_body_length. In the Linux kernel, all fragments for a single IP packet are stored into the same red-black tree (called an IP frag queue) until all fragments have been received. In order to filter out which fragment belongs at which offset when reassembling, the IP fragment offset is required: iph->offset = body_offset >> 3, whereby body_offset is the offset in the final IP body, and thus excluding any IP header lengths which may be used when calculating iph->len. As you may notice, fragment data has to be aligned with 8 bytes because the specs specify that the upper 3 bits of the offset field are used for flags (i.e. IP_MF and IP_DF). If we want to transmit 64 bytes of data across 2 fragments whose size are respectively 8 bytes and 56 bytes, we should format it like the code below. The kernel would then reassemble the IP packet as 'A' * 64.

iph1->len = sizeof(struct ip_header)*2 + 64;

iph1->offset = ntohs(0 | IP_MF); // set MORE FRAGMENTS flag

memset(iph1_body, 'A', 8);

transmit(iph1, iph1_body, 8);

iph2->len = sizeof(struct ip_header)*2 + 64;

iph2->offset = ntohs(8 >> 3); // don't set IP_MF since this is the last packet

memset(iph2_body, 'A', 56);

transmit(iph2, iph2_body, 56);Codeblock 2.3.1: C psuedocode describing the IP header format of IP fragments.

To learn more about packet fragmentation, check this blogpost by PacketPushers: "IP Fragmentation in Detail."

2.4. Page allocation

There are 3 major ways to allocate pages in the Linux kernel: using the slab-allocator, the buddy-allocator and the per-cpu page (PCP) allocator. In short: the buddy-allocator is invoked with alloc_pages(), can be used for any page order (0->10), and allocates pages from a global pool of pages across CPUs. The PCP-allocator is also invoked with alloc_pages(), and can be used to allocate pages with order 0->3 from a per-CPU pool of pages. Additionally, there's the slab-allocator, which is invoked with kmalloc() and can allocate pages with order 0->1 (including smaller allocations) from specialized per-CPU freelists/caches.

The PCP-allocator exists because the buddy-allocator locks access when a CPU is allocating a page from the global pool, and hence blocks another CPU when it wants to allocate a page. The PCP-allocator prevents this by having a smaller per-CPU pool of pages which are allocated in bulk by the buddy-allocator in the background. This way, the chance of page allocation blockage is smaller.

To learn more about the buddy-allocator and the PCP-allocator, check the Page Allocation section of this extensive analysis: "Reference: Analyzing Linux kernel memory management anomalies."

2.5. Physical memory

2.5.1. Physical-to-virtual memory mappings

One of the most fundamental elements of the kernel is memory management. When we are talking about memory, we could be talking about 2 types of memory: physical memory and virtual memory. Physical memory is what the RAM chips use, and virtual memory is how programs (including the kernel) running on the CPU interact with the physical memory. Of course when we use gdb to debug a binary, all addresses we use are virtual - since gdb and the underlying program is such a program as well.

Essentially, virtual memory is built on top of physical memory. The advantage of this model is that the virtual address range is larger than the physical address range - since empty virtual memory pages can be unmapped - which is good for ASLR efficiency among other things. Additionally, we can map 1 physical page to many virtual pages, or let there be an illusion that there are 128TiB addresses whilst in practice most of these are not backed by an actual page.

This means that we can work with 128TiB virtual memory ranges per process on a system with only 4GiB of physical memory. In theory, we could even map a single physical page of 4096 \x41 bytes to all 128TiB worth of userland virtual pages. When a program wants to write a \x42 byte to a virtual page, we perform copy-on-write (COW) and create a 2nd physical page and map that page to just the virtual page that the program wrote to.

In order to translate virtual memory addresses to physical memory addresses, the CPU utilizes pagetables. So when our userland program tries to read (virtual memory) address 0xDEADBEEF, the CPU will essentially do mov rax, [0xDEADBEEF]. However, in order to actually read the value from the RAM chips, the CPU needs to convert the virtual memory address 0xDEADBEEF to an physical memory address.

This translation is oblivious to the kernel and our userland program when it is trying to access a virtual memory address. To perform this translation, the CPU performs a lookup in the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) - which exists in the MMU - which caches the virtual-to-physical address translations. If the virtual 0xDEADBEEF address (or more specifically, the virtual 0xDEADB000 page) has been recently accessed, the TLB does not have to traverse the pagetables (the next section), and will have the physical address beloning to the virtual address in cache. Otherwise, if the address is not in the TLB cache, the TLB needs to traverse the pagetables to get the physical address. This will be covered in the next subsection.

To learn more about physical memory, check this excellent memory layout page from a Harvards Operating Systems course.

2.5.2. Pagetables

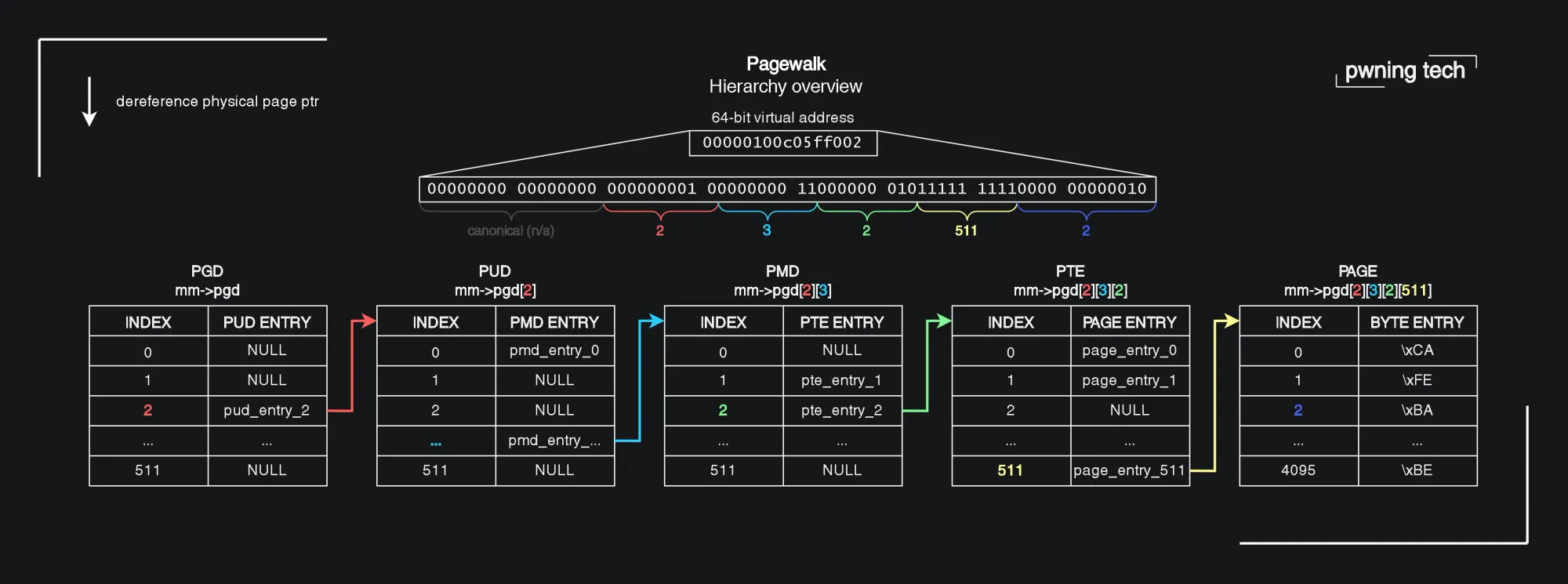

When the TLB gets requested a physical address for a virtual address which is not in its cache, it performs a "pagewalk" to acquire the physical address of a virtual address. A pagewalk means traversing the pagetables, which are a few nested arrays, with the physical addresses in the bottom arrays.

Note that the diagram below uses pagetable indices of 9 bits (because 2**9 = 512 pagetable values fit into a single page). Additionally, we are using 4-level pagetables here, but the kernel also supports 5-level, 3-level, et cetera.

This model of nested arrays is used because it saves a lot of memory. Instead of allocating a huge array for 128TiB of virtual addresses, it instead divides it into several smaller arrays with each layer having a smaller bailiwick. This means that tables responsible for an unallocated area will not be allocated.

Traversing the pagetables is a very inexpensive process since it are essentially 4-5 array dereferences. The indices for these dereferences are - get ready to have your mind blown - embedded in the virtual address. This means that a virtual address is not an address, but pagetable indices with a prefixed canonical. This elegant approach allows for O(1) physical address retrieval, since array dereferences are O(1) and the bit shifting to recover for the index is O(1) as well. Unfortunately, pagetables would need to be traversed very often which would make even these array dereferences slow. Hence, the TLB is implemented.

In terms of practicality, the TLB needs to find the pagetables in physical memory to pagewalk them. The address for the root of the userland pagetable hierarchy (PGD) of the running process is stored in the privileged CR3 register in the corresponding CPU core. 'Privileged' means that the register can only be accessed from kernelspace, as userland accesses will lead to a permission error. When the kernel scheduler makes the CPU switch to another process context, the kernel will set the CR3 register to virt_to_phys(current->mm->pgd).

To learn more about how the MMU finds the location of the pagetable hierarchy when the CPU needs to do a TLB lookup with cache miss, check the Wikipedia page on control registers.

2.6. TLB Flushing

TLB Flushing is the practice of, well, flushing the TLB. The translation lookaside buffer (TLB) caches translations between virtual addresses and physical addresses. This practice delivers a huge performance increase as the CPU doesn't have to traverse the pagetables anymore and can instead lookaside to the TLB.

When an virtual addresses' pagetable hierarchy changes in kernelspace, it needs to be updated in the TLB as well. This is invoked manually from the kernel by doing function calls in the same functions where the pagetables are changed. These functions "flush" the TLB, which empties the translation cache (possibly only for a certain address range) of the TLB. Then, the next the virtual address is accessed, the TLB will save the translation to the TLB cache.

However, sometimes we change the pagetables (and their virtual addresses) in exploits at times where that's not expected. An example of this is using a UAF write bug to overwrite a PTE. At that time, the TLB flushing functions in the kernel are not called, since we are not using the functions to change the page tables, which do invoke said functions. Hence, we need to flush the TLB indirectly from userland. Otherwise, the TLB would contain outdated cache entries. In the techniques section of this blogpost I present my own method of doing this.

To learn more about the TLB, check the Wikipedia article: "Translation lookaside buffer - Wikipedia."

2.7. Dirty Pagetable

Dirty Pagetable is a novel technique presented by N. Wu, which boils down to overwriting PTEs in order to perform an KSMA attack. Their research paper presents 2 scenarios to overwrite PTEs: a double-free bug and an UAF-write bug. Both scenarios are supplemented with a practical example. The original paper is definitely worth a read considering I learned a lot from it.

However, there are a few critical topics out-of-scope in the original paper, which I try to include in this blogpost. An example of those topics is how pagetables work, TLB flushing, proof-of-concept code, the workings of physical KASLR, and the format of PTE values. Additionally, I present a variation on this technique (Dirty Pagedirectory) in this blogpost.

To learn more, check the original research paper by N. Wu: "Dirty Pagetable: A Novel Exploitation Technique To Rule Linux Kernel."

2.8. Overwriting modprobe_path

One of the more classical privilege escalation techniques is overwriting the modprobe_path variable in the kernel. The value of the variable is set to CONFIG_MODPROBE_PATH at compile-time, and is padded to KMOD_PATH_LEN bytes with nullbytes. Usually CONFIG_MODPROBE_PATH is set to "/sbin/modprobe" as that is the usual filepath for the modprobe binary.

The variable is used when a user is trying execute a binary with an unknown magic bytes header. For instance, the magic bytes of an ELF binary are FE45 4C46 (a.k.a. ".ELF"). When executing the binary, the kernel will look for registered binary handlers which match said magic bytes. In the case of ELF, the ELF binfmt handler is selected. However when a registered binfmt is not recognized, modprobe will be invoked using the path stored in modprobe_path and it will query for a kernel module with the name binfmt-%04x, where %04x is the hex representation of the first 2 bytes in the file.

To exploit this, we can overwrite the value of modprobe_path with a string of the path of a privilege escalation script (which gives /bin/sh root SUID for instance), and then invoke modprobe by trying to execute a file with an invalid format such as ffff ffff. The kernel will then run /tmp/privesc_script.sh -q -- binfmt-ffff as root, which allows us to run any code as root. This saves us the hassle of having to run kernel functions ourselves, and instead allows easy privesc by overwriting a string.

Somewhere along the line, the CONFIG_STATIC_USERMODEHELPER_PATH mitigation was introduced, which makes overwriting modprobe_path useless. The mitigation works by setting every executed binary's path to a busybox-like binary, which behaves differently based on the argv[0] filename passed. Hence, if we overwrite modprobe_path, only this argv[0] value would differ, which the busybox-like binary does not recognize and hence would not execute.

The exploit presented in this exploit works both with and without CONFIG_STATIC_USERMODEHELPER_PATH, because we can simply overwrite the read-only "/sbin/usermode-helper" string in kernel memory.

To learn more about the modprobe_path technique, check this useful page on Github by user Smallkirby: "modprobe_path.md · smallkirby/kernelpwn."

2.9. KernelCTF

KernelCTF is a program ran by Google with the intent of disclosing new exploitation techniques for (hardened) Linux kernels. It's also a great way to get an ethical bounty for any vulnerabilities you may have in the Linux kernel, as the bounties range from $21.337 anywhere up to $111.337 and even more, all depending on the scope of the vulnerability and if there are any novel techniques.

The major outlines are that there are 3 machine categories: LTS (long-term stable kernel hardened with existing mitigations), mitigation (kernel hardened with experimental mitigations on top of existing mitigations), and COS (container optimized OS). Each machine can be hacked once per version, and the researcher who hacked the machine first gets the reward. This means that if researcher A hacked LTS version 6.1.63, then researcher A and researcher B can still hack mitigation version 6.1.63. After the next version is released on the KernelCTF platform (typically after 2 weeks), both researcher A and researcher B can hack LTS version 6.1.65 again. However, the bug reported by researcher A for version 6.1.63 will most likely be fixed now, and would be treated like a duplicate anyways if it were to be exploited again.

In order to "hack" the KernelCTF machine, the researcher needs to read the /flag file in the root (jail host) namespace, which is only readable by the root user. As you may expect, this may require both a namespace sandbox (nsjail) escape as well as an privilege escalation to the root user. At the end of the day, this does not matter as long as the flag is captured.

To debug the environment, check the local_runner.sh script which the KernelCTF team provides. Note the --root flag, which allows you to run a root shell from outside of the jail.

To learn more about the KernelCTF program, check this page: "KernelCTF rules | security-research."

3. The bug

3.1. Finding the bug

It all started when I wanted to implement firewall bypasses into my ORB rootkit Netkit. I wanted to rely on the kernel API (exported functions) for any actions, as it would have the same compatibility as regular kernel modules. Hopefully, this would mean that the rootkit kernel module could be used across architectures and kernel versions, without having to change the source code.

This led me into the rabbit hole called Netfilter. Before this research, I had no practical experience with Netfilter, so I had to do a lot of research on my own. Gladfully, there is plenty of documentation available from both the kernel developers and the infosec community. After reading myself into the subsystem, I read a bunch of source code from the top down related to nf_tables rules and expressions.

While reading nf_tables code - whose state machine is very interesting from a software development point of view - I noticed the nf_hook_slow() function. This function loops over all rules in a chain and stops evaluation (returns the function) immediately when NF_DROP is issued.

In the NF_DROP handling, it frees the packet and it allows a user to set the return value using NF_GET_DROPERR(). With this knowledge I made the function return NF_ACCEPT using the drop error when handling NF_DROP. A bunch of kernel panics and code path analyses later, I found a double-free primitive.

// looping over existing rules when skb triggers chain

int nf_hook_slow(struct sk_buff *skb, struct nf_hook_state *state,

const struct nf_hook_entries *e, unsigned int s)

{

unsigned int verdict;

int ret;

// loop over every rule

for (; s < e->num_hook_entries; s++) {

// acquire rule's verdict

verdict = nf_hook_entry_hookfn(&e->hooks[s], skb, state);

switch (verdict & NF_VERDICT_MASK) {

case NF_ACCEPT:

break; // go to next rule

case NF_DROP:

kfree_skb_reason(skb, SKB_DROP_REASON_NETFILTER_DROP);

// check if the verdict contains a drop err

ret = NF_DROP_GETERR(verdict);

if (ret == 0)

ret = -EPERM;

// immediately return (do not evaluate other rules)

return ret;

// [snip] alternative verdict cases

default:

WARN_ON_ONCE(1);

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}Codeblock 3.1.1: The nf_hook_slow() kernel function written in C, which iterates over nftables rules.

3.2. Root cause analysis

The root cause of the bug is quite simplistic in nature, as it is an input sanitization bug. The impact of this is a stable double-free primitive.

The important details of the dataflow analysis are that when creating a verdict object for a netfilter hook, the kernel allowed positive drop errors. This meant an attacking user could cause the scenario below, where nf_hook_slow() would free an skb object when NF_DROP is returned from a hook/rule, and then return NF_ACCEPT as if every hook/rule in the chain returned NF_ACCEPT. This causes the caller of nf_hook_slow() to misinterpret the situation, and continue parsing the packet and eventually double-free it.

// userland API (netlink-based) handler for initializing the verdict

static int nft_verdict_init(const struct nft_ctx *ctx, struct nft_data *data,

struct nft_data_desc *desc, const struct nlattr *nla)

{

u8 genmask = nft_genmask_next(ctx->net);

struct nlattr *tb[NFTA_VERDICT_MAX + 1];

struct nft_chain *chain;

int err;

// [snip] initialize memory

// malicious user: data->verdict.code = 0xffff0000

switch (data->verdict.code) {

default:

// data->verdict.code & NF_VERDICT_MASK == 0x0 (NF_DROP)

switch (data->verdict.code & NF_VERDICT_MASK) {

case NF_ACCEPT:

case NF_DROP:

case NF_QUEUE:

break; // happy-flow

default:

return -EINVAL;

}

fallthrough;

case NFT_CONTINUE:

case NFT_BREAK:

case NFT_RETURN:

break; // happy-flow

case NFT_JUMP:

case NFT_GOTO:

// [snip] handle cases

break;

}

// successfully set the verdict value to 0xffff0000

desc->len = sizeof(data->verdict);

return 0;

}Codeblock 3.2.1: The nft_verdict_init() kernel function written in C, which constructs an netfilter verdict object.

// looping over existing rules when skb triggers chain

int nf_hook_slow(struct sk_buff *skb, struct nf_hook_state *state,

const struct nf_hook_entries *e, unsigned int s)

{

unsigned int verdict;

int ret;

for (; s < e->num_hook_entries; s++) {

// malicious rule: verdict = 0xffff0000

verdict = nf_hook_entry_hookfn(&e->hooks[s], skb, state);

// 0xffff0000 & NF_VERDICT_MASK == 0x0 (NF_DROP)

switch (verdict & NF_VERDICT_MASK) {

case NF_ACCEPT:

break;

case NF_DROP:

// first free of double-free

kfree_skb_reason(skb,

SKB_DROP_REASON_NETFILTER_DROP);

// NF_DROP_GETERR(0xffff0000) == 1 (NF_ACCEPT)

ret = NF_DROP_GETERR(verdict);

if (ret == 0)

ret = -EPERM;

// return NF_ACCEPT (continue packet handling)

return ret;

// [snip] alternative verdict cases

default:

WARN_ON_ONCE(1);

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}Codeblock 3.2.2: The nf_hook_slow() kernel function written in C, which iterates over nftables rules.

static inline int NF_HOOK(uint8_t pf, unsigned int hook, struct net *net, struct sock *sk,

struct sk_buff *skb, struct net_device *in, struct net_device *out,

int (*okfn)(struct net *, struct sock *, struct sk_buff *))

{

// results in nf_hook_slow() call

int ret = nf_hook(pf, hook, net, sk, skb, in, out, okfn);

// if skb passes rules, handle skb, and double-free it

if (ret == NF_ACCEPT)

ret = okfn(net, sk, skb);

return ret;

}Codeblock 3.2.3: The NF_HOOK() kernel function written in C, which calls a callback function on success.

3.3. Bug impact & exploitation

As said in the subsection above, this bug leaves us with a very powerful double-free primitive when the correct code paths are hit. The double-free impacts both struct sk_buff objects in the skbuff_head_cache slab cache, as well as a dynamically-sized sk_buff->head object ranging from kmalloc-256 up to order 4 pages directly from the buddy-allocator (65536 bytes) with ipv4 packets (perhaps even more with ipv6 jumbo packets?).

The sk_buff->head object is allocated through a kmalloc-like interface (kmalloc_reserve()) in __alloc_skb(). This allows us to allocate objects of a dynamic size. Hence, we can allocate slab objects from size 256 to full-on pages of 65536 bytes from the buddy allocator. An functional overview of this can be found in the page allocaction subsection of the background info section.

The size of the sk_buff->head object is directly influenced by the size of the network packet, as this object contains the packet content. Hence, if we send a packet with e.g. 40KiB data, the kernel would allocate an order 4 page directly from the buddy-allocator.

When you try to reproduce the bug yourselves, the kernel may panic, even when all mitigations are disabled. This is because certain fields of the skb - such as pointers - get corrupted when the skb is freed. As such, we should try to avoid usage of these fields. Fortunately, I found a way to bypass all usage which could lead to a panic or usual errors and get a highly reliable double-free primitive. I'm highlighting this in the respective subsection within the proof-of-concept section.

3.4. Bug fixes

When I reported the bug to the kernel developers, I proposed my own bug fix which regretfully had to introduce a specific breaking change in the middle of the netfilter stack.

Thankfully, one of the maintainers of the subsystem came up with their own elegant fix. Their fix sanitizes verdicts from userland input in the netfilter API itself, before the malicious verdict is even added. The specific fix makes the kernel disallow drop errors entirely for userland input. The maintainer mentions however that if this behaviour is needed in the future, only drop errors with n <= 0 should be allowed to prevent bugs like these. This is because positive drop errors like 1 will overlap as NF_ACCEPT.

Additionally, the vulnerability was assigned CVE-2024-1086 (this was before the Linux kernel became an CNA and ruined the meaning of CVEs).

A use-after-free vulnerability in the Linux kernel's netfilter: nf_tables component can be exploited to achieve local privilege escalation.

The nft_verdict_init() function allows positive values as drop error within the hook verdict, and hence the nf_hook_slow() function can cause a double free vulnerability when NF_DROP is issued with a drop error which resembles NF_ACCEPT.

We recommend upgrading past commit f342de4e2f33e0e39165d8639387aa6c19dff660.Codeblock 3.4.1: The description of CVE-2024-1086.

--- a/net/netfilter/nf_tables_api.c

+++ b/net/netfilter/nf_tables_api.c

@@ -10988,16 +10988,10 @@ static int nft_verdict_init(const struct nft_ctx *ctx, struct nft_data *data,

data->verdict.code = ntohl(nla_get_be32(tb[NFTA_VERDICT_CODE]));

switch (data->verdict.code) {

- default:

- switch (data->verdict.code & NF_VERDICT_MASK) {

- case NF_ACCEPT:

- case NF_DROP:

- case NF_QUEUE:

- break;

- default:

- return -EINVAL;

- }

- fallthrough;

+ case NF_ACCEPT:

+ case NF_DROP:

+ case NF_QUEUE:

+ break;

case NFT_CONTINUE:

case NFT_BREAK:

case NFT_RETURN:

@@ -11032,6 +11026,8 @@ static int nft_verdict_init(const struct nft_ctx *ctx, struct nft_data *data,

data->verdict.chain = chain;

break;

+ default:

+ return -EINVAL;

}

desc->len = sizeof(data->verdict);

-- Codeblock 3.4.2: C code diff of the nft_verdict_init() kernel function being patched against the bug.

You can learn more about their fix on the kernel lore website: "[PATCH nf] netfilter: nf_tables: reject QUEUE/DROP verdict parameters."

4. Techniques

4.1. Page refcount juggling

The first technique required for the exploit is juggling page refcounts. When we attempt to double-free a page in the kernel using the dedicated API functions, the kernel will check the refcount of the page:

void __free_pages(struct page *page, unsigned int order)

{

/* get PageHead before we drop reference */

int head = PageHead(page);

if (put_page_testzero(page))

free_the_page(page, order);

else if (!head)

while (order-- > 0)

free_the_page(page + (1 << order), order);

}Codeblock 4.1.1: C code of the __free_pages() kernel function with original comments.

The refcount is usually 1 before we free the page (unless it is shared or something, then it is higher). If the pages' refcount is below 0 after it is decremented, it will refuse to free the page (put_page_testzero() will return false). This means that we shouldn't be able to double-free pages... unless?

The active readers will notice that several child-pages will then be freed until order-- == 0. However, after the first page free the page order is set to 0. Hence during the 2nd free where said code gets ran, no pages will be freed since order-- == -1. The fact that the page order gets set to 0 after a page free will be abused to convert the double-free pages to order 0 in the "Setting page order to 0" technique section.

In the context of a double-free: when we free the page for the 1st time, the refcount will be decremented to 0 and hence the page will be freed as the code above allows it to be. However, when we try free the page for 2nd time, the refcount will be decremented to -1 and it will not be freed since the refcount != 0 and may even raise a BUG() if CONFIG_DEBUG_VM is enabled.

So, how do we double-free pages then? Simple: allocate the page again before the 2nd free, as the free will look like a non-double-free free considering there is an actual object in the page. This can be any object with the same size, such as a slab or a pagetable, which is what I'm utilizing with the exploit.

In the most simplistic form, the implementation of this technique will look like this:

static void kref_juggling(void)

{

struct page *skb1, *pmd, *pud;

skb1 = alloc_page(GFP_KERNEL); // refcount 0 -> 1

__free_page(skb1); // refcount 1 -> 0

pmd = alloc_page(GFP_KERNEL); // refcount 0 -> 1

__free_page(skb1); // refcount 1 -> 0

pud = alloc_page(GFP_KERNEL); // refcount 0 -> 1

pr_err("[*] skb1: %px (phys: %016llx), pmd: %px (phys: %016llx), pud: %px (phys: %016llx)\n", skb1, page_to_phys(skb1), pmd, page_to_phys(pmd), pud, page_to_phys(pud));

}Codeblock 4.1.2: C code of a custom kernel module, containing comments describing page refcounts.

In terms of cleaning this up post-exploitation, it's incredibly easy: just free both objects at will, as the kernel will refuse to double-free the page because of the refcount. :-)

4.2. Page freelist entry order 4 to order 0

When an allocation happens through __do_kmalloc_node() (such as skb's), the size of the allocated object is checked against KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE (the maximum slab-allocator size). If the object is larger than that, one of the page allocators will be used instead of the slab-allocator. This is useful when we want to deterministically free pages like the skb data and allocate pages like PTE pages using the same algorithms and freelists. However, the value of KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE is equivalent to PAGE_SIZE * 2, which means that kmalloc will be using the page allocators for allocations above order 1 (2 pages, or 8096 bytes).

Unfortunately enough, some objects we may want to target are exclusively allocated by page allocators whilst still falling within the size of the slab-allocator. For example, a developer may use alloc_page() instead of kmalloc(4096), because this saves overhead. An example of this is a PTE page (or any other pagetable page for that sake), which uses page allocations of order 0 (1 page, or 4096 bytes).

If we would double-free an object of 4096 bytes (an order==0 page) handled by the slab-allocator, it would end up in the slabcaches, not in the pagecache. Hence, in order to double-alloc pages in the order==0 freelist, we need to convert the order 4 (16 page) freelist entries from our double-free to the order 0 (1 page) freelist entries.

Luckily, I found 2 methods to allocate order==0 pages with order==4 page freelist entries.

4.2.1. Draining the PCP list

This method takes advantage of the fact that the PCP-allocator is basically a set of per-CPU freelists for the buddy-allocator. When one of those PCP freelists are empty, it will refill pages from the buddy-allocator.

For a functional overview of the page allocation process (including if statements, and the slab-allocator and buddy-allocator), check the page allocation subsection in the background section.

The refill happens in bulks of count = N/order page objects. Hence, the function rmqueue_bulk() (which is used for the refill) allocates count pages with order order from the buddy-allocator. When allocating a page from the buddy-allocator, it will traverse the buddy page freelist, and if the buddy freelist entries' order >= order, then it will return this page for the refill. If the buddy freelist entries' order > order, then the buddy-allocator will internally divide the page.

Notice that our exploit double-free's order==4 pages, and needs to fill those with order==0 PCP pages. When we free it, the order==4 page is added to the buddy-freelist. For our exploit we want to place an order==0 page into these 16 pages, because the order==4 page will be double-freed. The allocation for order==0 pages happens with the PCP allocator, which has per-order freelists. However, the PCP-refill mechanism will take any buddy-page if it fits. Hence, we can allocate 16 PTE pages into the double-freed order==4 page.

As said, in order to trigger this mechanism we must first drain the PCP freelist for the target CPU by spraying page allocations. In my exploit I do this by spraying PTE pages, and this is directly related to the Dirty Pagedirectory technique. Because we cannot tell if the PCP freelist was drained, we need to assume one of the sprayed objects is allocated in the double-free object. Hence, I spray PTE objects so an PTE object takes the spot of one of the double-free'd buddy pages. If I wanted to allocate an PMD object, I would spray PMD objects, et cetera.

The amount of objects in the freelists differs per system and per resource usage. For the exploit I used 16000 PTE objects which is - in all cases I encountered - enough to empty the freelist.

static int rmqueue_bulk(struct zone *zone, unsigned int order,

unsigned long count, struct list_head *list,

int migratetype, unsigned int alloc_flags)

{

unsigned long flags;

int i;

spin_lock_irqsave(&zone->lock, flags);

for (i = 0; i < count; ++i) {

struct page *page = __rmqueue(zone, order, migratetype, alloc_flags);

if (unlikely(page == NULL))

break;

list_add_tail(&page->pcp_list, list);

// [snip] set stats

}

// [snip] set stats

spin_unlock_irqrestore(&zone->lock, flags);

return i;

}Codeblock 4.2.1.2: C code of the rmqueue_bulk() kernel function, which refills the PCP freelist.

4.2.2. Race condition (obsolete)

>> This technique is obsolete, but was used for kernelctf exploit <<

The first free() append the page to the correct freelist, and will set the page order to 0. However when doing a double-free (2nd free), the page will be added to the freelist for order 0 since that's what the page order is for that page. This way, we can add order==4 pages to the order==0 freelists with a double-free primitive.

Less luckily, this technique is a race condition. When a page is freed for the 2nd time without a intercepting alloc (free; free; alloc; alloc), the refcount of the page will drop below 0 and will not allow a double-free, so we need to do page reference juggling (free; alloc; free; alloc). However, then the order will not be 0 at the 2nd free, because the alloc will set the order to the original amount (i.e. order 4). Now, converting the page to order 0 seems impossible since it should be either no free at all (refcount -1), or the page being the original order (proper scenario). Enter: the race condition.

When a page is freed its order is passed by value. This means that if the double-freed page gets allocated during the 2nd free, it will be allocated to the freelist of order 0 and will have the refcount incremented, so it will not hit -1 and be 0 as it should be. As you can imagine, the race window is quite small since it consists of a few function calls. However, the free_large_kmalloc() function prints a kernel WARN() to dmesg if the order is 0, which it is because of the double-free. Usually, this only provides 1ms for the window, but for virtualized systems like QEMU VMs with serial terminals, the window is 50ms-300ms, which is more than enough to hit.

Now we have successfully attached the page the order 0 freelist, which means that we can now overwrite the page with any order-0 page allocation. We can also convert the 1st page reference (acquired with the 1st free) by freeing that object and reallocating it as a new object since the page order will persist. If we are using page refcount juggling, we want to free the object which took the first freed reference.

4.3. Freeing skb instantly without UDP/TCP stacks

When we are avoiding freelist corruption checks, we may want to free a certain skb directly at will at an arbitrary time, so our exploit can work in a very fast, synchronous manner with less chance of corruption.

Note that this behaviour is typically done with local UDP packets, but the skb gets corrupted after the first free in the double-free, which means I cannot use the TCP or UDP stacks for this, which utilized corrupted fields.

OBSOLETE (KERNELCTF EXPLOIT): Alternatively, we may want to free a certain skb on a specific CPU to bypass double-free detection, since the sk_buff freelist is per-CPU. This means that if we double-free an object across 2 CPUs directly after each other, the double-free will not be detected. We cannot "shoot the previous skb to the moon" (a.k.a. allocating a never expiring skb) to prevent double-free detection since this would alter the skb head pages by either changing the pointer, or by allocating the same pointer from the freelist preventing an double-free anyways.

Fortunately, IP packet fragmentation and its fragment queues exist. When an IP packet is waiting for all its fragments to be received, the fragments are placed into an IP frag queue (red-black tree). When the received fragments have the expected length of the full IP packet, the packet is reassembled on the CPU the last fragment came from. Please note that this IP frag queue has a timeout of ipfrag_time seconds, which will free all skb's. Changing this timeout is mentioned in the subsection hereafter.

If we wanted to switch the freelist of skb freelist entry skb1 from CPU 0 to CPU 1, we would allocate it as an IP fragment to a new IP frag queue on CPU 0. Then, we send skb2 - the final IP fragment for the queue on CPU 1. This causes skb1 to be freed on CPU 1.

This same behaviour can be used to free skb's at will, without using UDP/TCP code. This is benificient for the exploit, since the double-free packet is corrupted when it is freed for the first time. If we would use UDP code, the kernel would panic due to all sorts of nasty behaviour.

Unfortunately, the IP fragment queue's final size is determined by skb->len, which is fully randomized after the free due to overlaps with the slabcache's s->random. For details, check the next subsection. This means that it is practically impossible to complete the IP frag queue consistently because it will use a random expected length.

Hence, I came up with a different strategy: instead of completing the IP frag queue we make it raise an error using invalid input. This will cause all skb's in the IP frag queue to be freed instantaneously on the CPU of the erroring skb, regardless of skb->len.

When implementing this technique yourself, note that double-free detection (CONFIG_FREELIST_HARDENED) will be triggered if you do not append "innocent" skb objects between freeskb1and allocskb2. For demonstrative purposes these have been left out in the diagram, but are included in the PoC sections.

4.3.1. Modifying skb max lifetime

For our exploit we may want skb's to live shorter or longer, depending on the usecase. Luckily, the kernel provides an userland interface to configure IP fragmentation queue timeout times over at /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ipfrag_time. This is specific per network namespace, and can hence be set as unprivileged user in their own networking namespace.

When we use IP fragments to reassemble an split IP packet, the kernel will wait ipfrag_time seconds before issuing a timeout. If we set ipfrag_time to 999999 seconds, the kernel will let the fragment skb live for 999999 seconds. Invertedly, we can also set it to 1 second if we want to swiftly allocate and deallocate an skb on a random CPU.

static void set_ipfrag_time(unsigned int seconds)

{

int fd;

fd = open("/proc/sys/net/ipv4/ipfrag_time", O_WRONLY);

if (fd < 0) {

perror("open$ipfrag_time");

exit(1);

}

dprintf(fd, "%u\n", seconds);

close(fd);

}Codeblock 4.3.1.1: C code of an userland function to set the ipfrag_time variable.

4.4. Bypassing KernelCTF skb corruption checks

The only mitigation I had to actively bypass in the KernelCTF mitigation instance were freelist corruption checks, specifically the one that checks if the freelist next ptr in an object being allocated is corrupted.

Unfortunately, the freelist next ptr overlaps with skb->len since skbuff_head_cache->offset == 0x70. This means that the next/previous freelist entry pointer is stored at sk_buff+0x70, which coincidentally overlaps with skb->len. Online sources told me s->offset is usually set to half the slab size by kernel developers to avoid OOB writes from being able to overwrite freelist pointers, which in the past led to easy privesc using OOB bugs.

After the 1st skb free, the skb->len field gets overwritten with a partial next ptr value. In the code leading up to skb's 2nd free, the skb->len field gets modified because of packet parsing. Hence, the freelist next ptr gets corrupted even before the 2nd skb free.

When we try to allocate the freelist entry of the 1st skb free (after said corruption) using slab_alloc_node(), the freelist next ptr in the freed object gets flagged for corruption in calls invoked by freelist_ptr_decode():

static inline bool freelist_pointer_corrupted(struct slab *slab, freeptr_t ptr,

void *decoded)

{

#ifdef CONFIG_SLAB_VIRTUAL

/*

* If the freepointer decodes to 0, use 0 as the slab_base so that

* the check below always passes (0 & slab->align_mask == 0).

*/

unsigned long slab_base = decoded ? (unsigned long)slab_to_virt(slab) : 0;

/*

* This verifies that the SLUB freepointer does not point outside the

* slab. Since at that point we can basically do it for free, it also

* checks that the pointer alignment looks vaguely sane.

* However, we probably don't want the cost of a proper division here,

* so instead we just do a cheap check whether the bottom bits that are

* clear in the size are also clear in the pointer.

* So for kmalloc-32, it does a perfect alignment check, but for

* kmalloc-192, it just checks that the pointer is a multiple of 32.

* This should probably be reconsidered - is this a good tradeoff, or

* should that part be thrown out, or do we want a proper accurate

* alignment check (and can we make it work with acceptable performance

* cost compared to the security improvement - probably not)?

*/

return CHECK_DATA_CORRUPTION(

((unsigned long)decoded & slab->align_mask) != slab_base,

"bad freeptr (encoded %lx, ptr %p, base %lx, mask %lx",

ptr.v, decoded, slab_base, slab->align_mask);

#else

return false;

#endif

}Codeblock 4.4.1: C code of the kernel function freelist_pointer_corrupted() (KernelCTF mitigation instance), including the original comments.

After some research, I figured out that this check is not ran retroactively: when we free an object on top of the object with a corrupted freelist entry, the mitigation does not check if the previous object has a corrupted next ptr. This means that we can mask an invalid next ptr by freeing another skb after it, and then allocate that skb again with the data of the old skb. This basically masks the original corrupted skb, whilst still being able to double-alloc the skb data.

The diagram below tries to explain this phenomenon by performing a double-free on an skb object like the exploit in this blogpost.

The KernelCTF devs could mitigate this by checking the freelist head next ptr for corruption when freeing, not only when allocating.

4.5. Dirty Pagedirectory

4.5.1. The train of thought

Dirty Pagetable is one of the most interesting techniques I have encountered so far. When I was researching ready-made techniques to exploit the double-free bug Dirty Pagetable came to surface, and it seemed like a perfect technique.

However I did realize that consistent writing to the PTE page would be an unpleasant experience in the context of my double-free bug. I was unable to find any page-sized objects which allowed to be fully overwritable with userdata, whilst also being in the same page freelist as the PTE pages. I did not want to use cross-cache attacks for stability and compatiblity related reasons, as this would introduce more complexity into the exploit.

Next came a night full of brainstorming which gave me the following idea: considering I have a double-free in the same freelist as PTEs - what if it were possible to double allocate PTEs across processes, such as sudo and the exploit. This would essentially perform memory sharing (pointing the exploit virtual addresses to sudo's physical addresses) between the two completely unrelated processes. Hence, it would presumably be possible to manipulate the application data of an process running under root, and leverage that for a root shell. This turned out to be a bit unpractical considering there were other allocations happening as a process gets started, so there would need to be very good position management on the freelist.

This gave me the next idea: what if it were possible to double-allocate an exploit PTE page and an exploit PMD page, as this would mean that the PMD would dereference the PTE's page (as PTE value) as PTE and hence resolve the PTE's userland pages as PTE.

Fortunately enough, this PMD+PTE approach works. Alternatives such as PUD+PMD have been confirmed working as well, and perhaps PGD+PUD works too. The only difference is the amount of pages simulationously mirrored: 1GiB pages with PTE+PMD, 512GiB with PUD+PMD, and presumably 256TiB with PGD+PUD (if this is even possible). Keep in mind that this has impact on memory usage, and the system may go OOM with too much memory mirrored.

Additionally, the integration of Dirty Pagedirectory needs to be considered when choosing between PMD+PTE and PUD+PMD. I explain this in the PTE spraying section, but in general PMD+PTE should be the best choice.

4.5.2. The technique

The Dirty Pagedirectory technique allows unlimited, stable read/write to any memory page based on physical addresses. It can bypass permissions by setting its own permission flags. This allows our exploit to write to read-only pages like those containing modprobe_path.

In this section I explain PUD+PMD, but it boils down to the same as the PMD+PTE strategy from the PoC exploit.

The technique is quite simplistic in nature: allocate a Page Upper Directory (PUD) and Page Middle Directory (PMD) to the same kernel address using a bug like a double-free. The VMAs should be seperate, to avoid conflicts (a.k.a. do not allocate the PMD within the area of the PUD). Then, write an address to the page in the PMD range and read the address in the corresponding page of the PUD range. The diagram below tries to explain this phenomenon (complementary to the example under it).

To make things more hands-on, let's imagine the following scenario: the infamous modprobe_path variable is stored in a page at PFN/physical address 0xCAFE1460. We apply Dirty Pagedirectory: double-allocate the PUD page and PMD page via mmap for respective userland VMA ranges 0x8000000000 - 0x10000000000 (mm->pgd[1]) and 0x40000000 - 0x80000000 (mm->pgd[0][1]).

This automatically means that mm->pgd[1][x][y] is always equal to mm->pgd[0][1][x][y] because both mm->pgd[1] and mm->pgd[0][1] refer to the address/object as we double-allocated them. Observe how mm->pgd[0][1][x][y] is a userland page, and that mm->pgd[1][x][y] is a PTE. This means that the dedicated PUD area will interpret a userland page from the PMD area like a PTE.

Now, to read the physical page address 0xCAFE1460 we set first entry of the PUD areas' PTE value to 0x80000000CAFE1867 (added PTE flags) by writing that value to 0x40000000 (a.k.a. userland address for page @ mm->pgd[0][1][0][0]+0x0). Because of the entanglement rule above, this means that we wrote that value to the PTE address for page @ mm->pgd[1][0][0]+0x0, since mm->pgd[1][0][0] == mm->pgd[0][1][0][0]. Now, we can dereference that malicious PTE value by reading page mm->pgd[1][0][0][0] (last index 0 since we wrote it to the first 8 bytes of the PTE: notice 0x0 above). This is equal to userland page 0x8000000000.

Because the PTE is now changed from userland, we need to flush the TLB because the TLB will contain outdated record. Once that's done, printf('%s', 0x8000000460); should print /sbin/modprobe or whatever value modprobe_path is. Naturally, we can now overwrite modprobe_path by doing strcpy((char*)0x8000000460, "/tmp/privesc.sh"); (there's KMOD_PATH_LEN bytes padding) and drop a root shell. This does not require TLB flushing because the PTEs themselves have not changed when writing to the address.

Observe how we set the read/write flags in PTE value0x80000000CAFE1867. Note that0x8in virtual address0x8000000460and PTE value0x80000000CAFE1867has nothing to do with each other: in the PTE value it is a flag turned on, and the virtual address just happens to start with0x8.

This boils down to: write PTE values to userland pages in the VMA range of 0x40000000 - 0x80000000, and dereference them by reading and writing corresponding userland pages in the VMA range of 0x8000000000 - 0x10000000000.

4.5.3. The mitigations

I have used this technique to bypass a lot of mitigations currently in the kernel (among others: virtual KASLR, KPTI, SMAP, SMEP, and CONFIG_STATIC_USERMODEHELPER), albeit other mitigations are bypassed in the PoC exploit with a little redneck engineering.

When this technique was peer-reviewed I got asked how it was able to bypass SMAP. The answer is quite simple: SMAP only works with virtual addresses and not for physical memory addresses. PTEs are referred to in PMDs by their physical address. This means that when a PTE entry in a PMD is a userland page, it will not be detected by SMAP because it is not a virtual addresses. Hence, the PUD area can happily use the userland page as a PTE without SMAP intereference.

It would be possible to mitigate this technique by setting an table entries' type in the entry and use it to detect when a PMD is allocated on the place of an PUD since we cannot forge PMD entries and PUD entries themselves. An example is setting type 0 for PTEs, 1 for PMDs, 2 for PUDs, 3 for P4Ds, 4 for PGDs, et cetera. However, this would require 2log(levels) bits to be set in each table entry (3 bits when P4D is enabled, since levels=5) which would sacrifice space intended for features in the future, as well as the runtime checks presumably introducing a great deal of overhead since each level for each memory access has to be checked. Additionally, this mitigation would still allow for forced memory sharing (i.e. overlapping an exploit PTE page with an PTE page of sudo, running as root).

4.6. Spraying pagetables for Dirty PD

You may notice that that the Dirty Pagedirectory section above mentions PUD+PMD, but the proof-of-concept uses PMD+PTE. This is related to the fact that the exploit drains the PCP list to allocate a PTE in the double-free'd address.

First off, pagetables are allocated by the kernel on demand, so if we mmap'd a virtual memory area the allocation does not happen. Only when we actually read/write this VMA it will allocate the required pagetables for the accessed page. When allocating a PUD for instance, the PMD, PTE, and userland page will be allocated. When allocating a PTE, the target userland page will also be allocated.

The original Dirty Pagetable paper mentions that - very elegantly - you can spray specific pagetable levels by allocating the parents first, since a parent (i.e. PMD) contains 512 children (PTEs). Hence, if we wanted to spray 4096 PTEs, we would need to pre-allocate 8 (4096/512 = 8) PMDs, before allocating the PTEs.

If we spray PMDs, the PTEs will be allocated as well - from the same freelist. This means that 50% of the spray is PMD, and 50% is PTE. If we would spray PUDs, it would be 33% PUD, 33% PMD, and 33% PTE. Hence, if we spray PTEs, it will be 100% PTE since we are not doing any other allocations. Because of this, we use PMD+PTE in the exploit and not PUD+PMD, and spraying PMDs means 50% less stability.

Note that userland pages themselves are allocated from a different freelist (migratetype 0, not migratetype 1).

4.7. TLB Flushing

TLB flushing is the practice of removing or invalidating all entries in the translation lookaside buffer (virtual address to physical address caching). In order to scan addresses reliably using the Dirty Pagedirectory technique, we need to come up with a TLB flushing technique that satisfies the following requirements:

- Does not modify existing process pagetables

- Has to work 100% of the time

- Has to be quick

- Can be triggered from userland

- Has to work regardless of PCID

Based upon these requirements I came up with the following idea: when allocating PMD and PTE memory areas you should mark them as shared, and then fork() the process, make the child munmap() it for a flush, and make the child go to sleep (to avoid crashes if the underlying exploit is unstable). The result is the following function:

static void flush_tlb(void *addr, size_t len)

{

short *status;

status = mmap(NULL, sizeof(short), PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

*status = FLUSH_STAT_INPROGRESS;

if (fork() == 0)

{

munmap(addr, len);

*status = FLUSH_STAT_DONE;

PRINTF_VERBOSE("[*] flush tlb thread gonna sleep\n");

sleep(9999);

}

SPINLOCK(*status == FLUSH_STAT_INPROGRESS);

munmap(status, sizeof(short));

}Codeblock 4.7.1: C code of an userland function which flushes the TLB for a certain virtual memory range.

The locking mechanism prevents the parent from continuing execution before the child has flushed the TLB. It could presumably be removed if the child performs a process exit instead of sleeping, as the parent could monitor for the childs process state.

This TLB flushing method has worked 100% of the times to refresh pagetables and pagedirectories. It has been tested on a recent AMD CPU and in QEMU VMs. It should be hardware independent, since the flush HAS to be triggered from the kernel in this usecase.

4.8. Dealing with physical KASLR

Physical Kernel Address Space Layout Randomization (Physical KASLR) is the practice of randomizing the physical base address of the Linux kernel. Usually, this is not important since nearly all exploits work with virtual memory (and therefore have to deal with virtual KASLR).

However, because of the nature of our exploit - which utilizes Dirty Pagedirectory - we need to have the physical address of the memory we want to read/write to.

4.8.1. Getting the physical kernel base address

Usually, this means we would need to bruteforce the entire physical memory range to find the physical target address.

Physical memory refers to all forms usable of physical memory addresses: e.g. on a laptop 16GiB RAM stick + 1GiB builtin MMIO = 17GiB physical memory on the device.

However, one of the quirks of the Linux kernel is that the physical kernel base address has to be aligned to CONFIG_PHYSICAL_START (i.e. 0x100'0000 a.k.a. 16MiB) bytes if CONFIG_RELOCATABLE=y. If CONFIG_RELOCATABLE=n, the physical kernel base address will be exactly at CONFIG_PHYSICAL_START. For this technique, we assume CONFIG_RELOCATABLE=y, since it would not make sense to bruteforce physical KASLR if we knew the address.

IfCONFIG_PHYSICAL_ALIGNis set, this value will be used for the alignment instead ofCONFIG_PHYSICAL_START. Note thatCONFIG_PHYSICAL_ALIGNis usually smaller, like0x20'0000a.k.a. 2MiB, which means more addresses need to be bruteforced (8 times more than with an alignment of0x100'0000).

Assuming the target device has 8GiB physical memory, this means that we can reduce our search area to 8GiB / 16MiB = 512 possible physical kernel base addresses since we know the base address has to be aligned to CONFIG_PHYSICAL_START bytes. The advantage is that we only have to check the first few bytes of the first page of the 512 addresses to check if that page is the kernel base.

We can essentially figure out the physical kernel base address by bruteforcing a few hundred physical addresses. Fortunately, Dirty Pagedirectory allows for unlimited read/writes of entire pages, and hence allows us to read 4096 bytes per physical (page) address, and even more fortunately 512 page addresses per PTE overwrite. This requires us to only overwrite the PTE once to figure out the physical kernel base address if our machine has 8GiB memory.

In order to properly recognize which of those 512 physical addresses contains the kernel base, I have written get-sig: a few Python scripts to generate a giant memcmp-powered if statement which finds overlapping bytes between different kernel dumps.

4.8.2. Getting the physical target address

When we find the physical base address, we can find the final target address of our read/write operation - if it resides within the kernel area - using hardcoded offsets based on the physical kernel base, or by scanning the ~80MiB physical kernel memory area for data patterns of the target.

The data scanning technique requires 1 + 80MiB/2MiB ~= 40 PTE overwrites on a system with 8GiB memory. If we have access to Dirty Pagedirectory and the format of the target data is unique (like modprobe_path's buffer), the data pattern scanning method is better due to broader compatibility across kernel versions, and especially if we do not know the offsets when compiling the exploit.

Please note ~80MiB for the memory scanning technique is an estimation and will probably be less in reality, and it can even be optimized to a smaller memory area because certain targets may reside at certain areas which have a certain offset. For example, kernel code may appear from offset +0x0 from the base address, whilst kernel data may always start from e.g. +0x1000000 regardless of the kernel used because the kernel size remains pretty consistent. Hence, if we were searching for modprobe_path, we could simply start at +0x1000000, but this has not been tested.

5. Proof of Concept

5.1. Execution

Let's breach the mainframe, shall we? The general outlines of the exploit can be derived from the diagram below. In this section I'm trying to link the subsections to this diagram for clarity.

Note that the exploit in this section refers to the new version, not the original KernelCTF mitigation exploit (the new one works on the mitigation instance as well). That write-up will be published seperately in the KernelCTF repository.

Feel free to read along with the source code of the exploit, which is available in my CVE-2024-1086 PoC repository.

5.1.1. Setting up the environment